In an archival experiment of historic proportions, professor emeritus Dr. Richard Crepeau of the UCF history department challenged his students in the spring and summer of 1976 to amass a collection of ephemera highlighting the profusion of the American bicentennial celebrations. Items ranging from the predictable to the more unique permeated American markets and found their way into the hearts of American homes and families. Recognizing the significance of the items in the bicentennial collection and their reach in terms of leisure and entertainment, home and family, and travel and education hints at broader social trends and reveals conflicting truths about life in the United States in 1976.

Many of the items in Dr. Crepeau’s bicentennial collection are household in nature. Looking beyond the perishable, disposable, temporary pieces like sugar packets and cereal boxes, the eye comes to rest on a handful of more durable, reusable items intended for accumulation and display. There are a handful of tea towels in the collection, items with a distinctly British heritage that have been rebranded with robust American iconography and employed for prolonged use in the kitchen of millions of homes across the nation. They are both decorative and functional, intended to remind the user of their patriotism every time a dish is dried.

[Left: full-size tea towel decorated with eagle emblems, Revolutionary War soldiers, bells, drums, and tall ships. Right: placemat-size tea towel with 10 images celebrating events associated with 1776, middle graphic reads “Patriots then and now, from sea to shining sea, a salute to America’s 200 years.”]

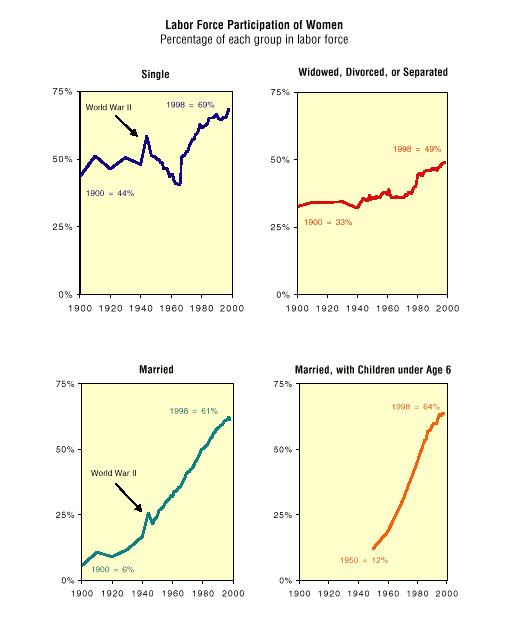

Employing household pieces like these tea towels in the commemoration of the bicentennial hints at the intended domesticity of the 1970s and places the kitchen at the heart of the home and the ideal American family during the Cold War era. This focus stands in stark contrast to the status of women in light of emerging social movements, including that of feminists and other such groups embracing Abigail Adams’ famous insistence that America “Remember the Ladies.” By 1976, the American divorce rate as well as the number of married women with school-aged children in the labor force exceeded 50 percent. [1] “[Census] data painted a picture of the United States in which the nuclear family once featured on the pages of Life was becoming less and less common at the same time that new family forms – families shaped by divorce and separation, single parenthood, and dual wage earning – were becoming more viable.”[2]

[Labor Force Participation of Women, http://www.pbs.org/fmc/book/2work8.htm]

[Labor Force Participation of Women, http://www.pbs.org/fmc/book/2work8.htm]

To keep up with such changes in family structure and advances in employment opportunities, women began engaging in various forms of social activism outside the home designed to promote gender equality and eradicate discrimination in a variety of social and professional settings. Drawing inspiration from the first wave feminists of the 1920s, groups like the National Organization for Women (NOW), the Women’s Equity Action League, the Y.W.C.A., the Girls Clubs of America and even some Junior Leagues began engaging in various forms of social activism. Names like Gloria Steinem, Betty Friedan, Susan Brownmiller, and Kate Millet came to dominate public discourse, despite backlash from a variety of men, conservatives, and the infamous Phyllis Schlafly, a conservative activist and leader of the Anti-ERA lobby. Schlafly, a visibly liberated woman with a law degree from Washington University in St. Louis, claimed the bill “conjured up the prospect of unisex public toilets, an end to alimony, and women forced into duty as combat soldiers.” [3]

[Left: The feminist greats Gloria Steinem, Bella Abzug, Shirley Chisholm, and Betty Freidan (Charles Gorry/AP). Right: The late Phyllis Schlafly at a 1976 anti-ERA meeting (Associated Press)]

The efforts of these radical women standing up in the face of oppression and relegation to the domestic sphere (with its quaint tea towel kitchens) led to victories like the legalization of birth control for everyone, including non-married individuals, in 1972, the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, a landmark case in the push for women’s reproductive freedom, and the progression of The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA). By 1975, it was only four states away from ratification. [4] The very same year, Time magazine awarded its man of the year to “American women” collectively, a victory followed up by a lengthy article entitled “Great Changes, New Chances, Tough Choices”[4] in its first issue of 1976, just five months before the beginning of American bicentennial celebrations. What started as grassroots resistance had blossomed into a movement that fundamentally changed what it meant to be a woman in the United States in the 1970s.

[Left: Picketing the Miss America Pageant, 1968. Right: Pittsburgh Protests for the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, 1976]

For a select few, the bicentennial stood to highlight consciously overlooked racial and gendered inequality present in the United States since its founding two hundred years before. Prototypical patriotism was mass-produced and disseminated in the form of items like these tea towels, celebrating unity, allegiance, and a somewhat subconscious embrace of conformity with acceptable social constructs that many were actively working to reject. Thanks to the privileged majority, however, the bicentennial would come to be remembered as the perfect rallying point for the refocusing of a cohesive American people in the face of Cold War tumult, reviving “the nineteenth-century idea of history as rarefied…in the service of Cold War nationalism.” [5]

By highlighting such pieces as the tea towels and placing them within the larger context of the bicentennial celebrations and changing notions of social life in the United States in the months and years surrounding July 1976, staunch contrasts between idealized American living and the realities of struggle and marginalization, especially for women regardless of race, sexual orientation, or social standing, become clear. There is much more to this complex history than is presented here, but even a broad overview like this one seeks to tell stories within the larger scope of the 1970s, allowing for an inclusive yet focused approach to historical exposé. Themes of domesticity and gender roles, advertising trends and branding ability, and consumer behavior – along with their counter-movements – can all be interpreted through a closer study of these seemingly inconspicuous items in Dr. Crepeau’s bicentennial collection.

[1] US Bureau of the Census. Statistical Abstract of the United States: 1976. (97th edition.) Washington, D.C., 1976. Accessed October 17, 2016. http://www.census.gov/library/ publications/1976/compendia/statab/97ed.html.

[2] Natasha Zaretsky, No Direction Home: The American Family and the Fear of National Decline, 1968-1980 (Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 2010), 11.

[3] Ryan Bergeron, “‘The Seventies’: Feminism Makes Waves,” CNN, August 17, 2015, accessed October 17, 2016, http://www.cnn.com/2015/07/22/living/the-seventies-feminism-womens-lib/.

[4] “Women of the Year: Great Changes, New Chances, Tough Choices,” Time, Jan 5, 1976, http://content.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,947597-1,00.html.

[5] Tammy S. Gordon, The Spirit of 1976: Commerce, Community, and the Politics of Commemoration (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013), 47.

See also:

Bosek, Ruth A., Meredith McCain, and Mildred L. Rogers. Women Involved: A Report on the Bicentennial Achievements of Women. Washington, D.C.: American Revolution Bicentennial Administration, 1976.

Geisel, EllynAnne. The Kitchen Linens Book: Using, Sharing, and Cherishing the Fabrics of Our Daily Lives. New Jersey: Andrews McMeel Publishing, 2009.

Kendrick, K. “Roe v. Wade and its Effects on Society.” Rollins College. Accessed October 17, 2016. http://social.rollins.edu/wpsites/thirdsight/2014/02/10/roe-v-wade-and-its-effects-on-society/.

“The Women’s Rights Movement.” In American Social Reform Movements Reference Library, edited by Carol Brennan, Kathleen J. Edgar, Judy Galens, and Roger Matuz, 373-405. Vol. 2, Almanac. Detroit: UXL, 2007. U.S. History in Context (accessed October 17, 2016).