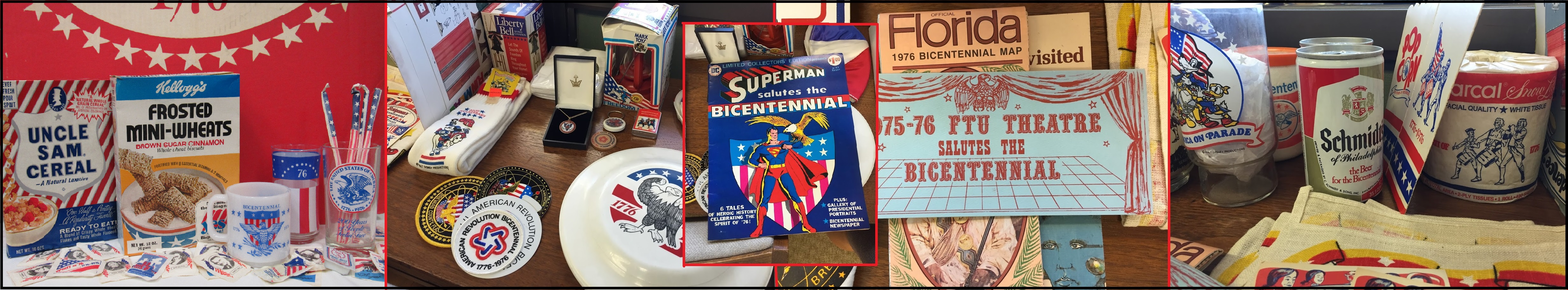

I would like to highlight items that show no real affiliation with specific interests; in other words generic items (sugar packets, jelly packets, grocery bags, toilet paper, soap). Tammy S. Gordon emphasizes in her book The Spirit of 1976: Commerce, Community, and Commemoration that weather American citizens sat on either the right, or the left both were heavily involved in the “spirit” and consumerism of these products[1]. To create this environment, advertisers would have to generate mass appeal on a base level. This was difficult because during the bicentennial, there was concern about hitting three profitable groups of the time: African Americans, youths, and urban shoppers. Such an emphasis on “Americana related themes” would alienate these groups who provided the most skepticism and cynicism concerning American patriotism[2]. This coupled with a marketplace plastered with bicentennial memorabilia made was difficult to stick out; a simplistic solution to these problems was forced participation

A perfect example of this technique is the sugar and jelly packets. First of all, these are generic ingredients that are found in most restaurants and homes, which would make them difficult to avoid. Second, these items are very different from other items in the collection (magazines, beer, soda, socks, or toys). The packets do not require some kind of interest level like magazines, or an age restriction like beer, or interest in hobbies like the kite. These are standard items that can not only be put on food, but can also be a massive display. The skeptical groups might not buy the commemorative plate, coffee can, or kite; but things like these small food packets made it very difficult to escape consuming bicentennial memorabilia.

This idea of “forced participation” can be seen when looking at items like the grocery bags as well. Looking at this collection it is hard to believe one could go to the store and buy “alternative” items that do not have to do with the bicentennial celebration. If they were able to accomplish this, they might be in for a surprise when all of their items would be placed in a bicentennial grocery bag. This utilization of marketing is genius because it requires little work on the seller while the consumer is being indoctrinated with patriotic memorabilia. Even if they are unwilling.

These products are also untouched which made it easier to produce. If you wanted to read an issue of MAD, Time, or Newsweek the content of that magazine would be altered due to the bicentennial. The Plate no longer serves its use outside of independence themed holidays. But the taste of the sugar does not change, the grape jelly does not change; just the packaging. Plus it is small enough to forgive someone if they still had leftover packets after the bicentennial celebration.

Another example of this is commemorative, bicentennial toilet paper. The only thing “bicentennial” about it is the wrapping on the outside of the paper. It is still just plain, white, toilet paper otherwise. Once that package is off it no longer has affiliation with the bicentennial, yet one would still be participating in the mass consumerism.

Items like condiment packets, toilet paper, and soap also have a long shelf life. Magazines are no longer topical and other consumables do not have as many units inside a package (i.e. only a 6 pack of soda). This means that long after the bicentennial was over, people were still using these products and therefore being further indoctrinated with the patriotism that the company perpetuated.

With the political climate the way it was in 1976 it was important for companies to create products that appealed to all walks of life. The idea to use products as small as sugar packets to endorse the bicentennial shows the permeation of the subject matter. Bicentennial endorsement was ubiquitous and inescapable. Not all products would be consumed by everybody, but these products covered the most bases. These do not require an age or interest to use, they could be in your cabinet, in your fast food restaurant, or garbage lying on the ground. The ability to be used by the possible unwilling, while also being seen by a mass audience is what makes these products so vital in understanding the goals and saturation of bicentennial memorabilia products.

[1] Gordon, Tammy S. The Spirit of 1976: Commerce, Community, and Commemoration (Massachusetts: University of Massachusetts Press, 2013) Pg. 18

[2]ibid, Pg 48

How Exhibits Can Be Used As Learning Mechanisms

How Exhibits Can Be Used As Learning Mechanisms

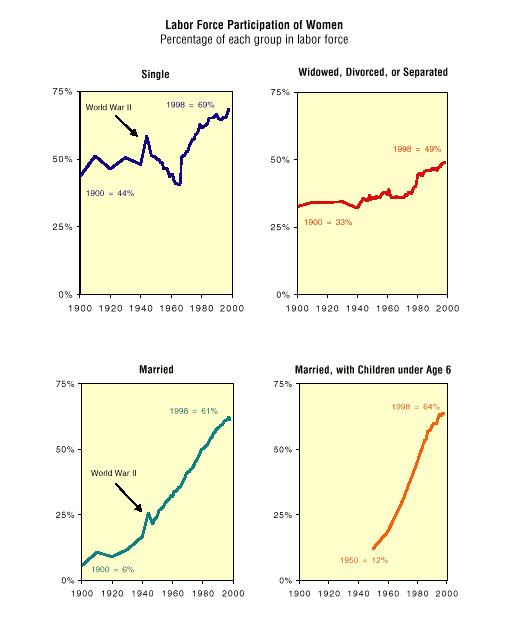

[Labor Force Participation of Women, http://www.pbs.org/fmc/book/2work8.htm]

[Labor Force Participation of Women, http://www.pbs.org/fmc/book/2work8.htm]